The Benefits of the Ear to Instrument Connection

I recently watched a video performance by the amazing classical pianist Yuja Chang. I’ve seen her memorizing motion and heard her virtuosic playing before, but something hit me after seeing

Categories:

Categories:

This is the final part of a six-part series on why and how to expand beyond the narrow ranges of dynamics, notes, articulations, rhythms, and phrase lengths. Harmonic range is an important element of this series because most instruction on improvisation focuses almost exclusively on the scales within the diatonic harmony of the chords. In other words, staying exclusively within the “correct” notes of the chord progression.

When first starting out improvising, we need to “walk” before we can “run”, so we learn the associated scales for each chord type and key. That’s appropriate, but the problem becomes that too few players ever go beyond that diatonic association to explore the notes outside of those “right” notes of the chord progression. In truth, you can play any of the 12 notes over any chord. As I’ve said many times within my blog, books, and courses, your choice of notes is contextual. So let’s explore a bit about what we’ll call chromaticism, or the idea of playing notes outside of the strict diatonic harmony of the chord progression.

For this attribute of improvisation, I thought I’d ask an expert on jazz harmony, LeeAnn Ledgerwood, to contribute to this post.

LeeAnn has been on the faculties of Mannes College of Music and the New School for Jazz and Contemporary Music since 1992. She was the first of only two members of the jazz faculty to ever receive the prestigious Distinguished University Teacher Award in 1997 from Mannes College and the New School Jazz divisions. Currently LeeAnn is completing a book on Advanced Reharmonization which is in tandem with the course that she teaches at the New School where she continues to teach jazz piano and composition.

When introducing chromaticism to students of jazz improvisation, there are two ways to approach the subject which has proven helpful to the many students I have taught over the years.

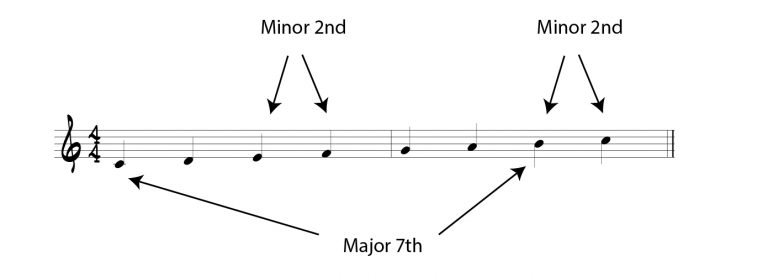

The first way is to realize that as jazz players, we are already dealing with chromaticism. Simply put, chromaticism exists in a Minor 2nd interval, a Major 7th, and Minor 9th intervals. In a major scale, it occurs between the 3rd and 4th step, and the 7th and 8th step.

In teaching beginning theory, the harmonization of scales extends up to create triads.

In jazz theory, our treatment of harmony extends past triads into the 7th and even 9th chords. Those extended structures provide more tones for us to cross the bridge into chromaticism.

Chromaticism is not something foreign or out of reach since our experiences with just a major scale allows us to experience working with chromaticism. Taking this in a linear context, chromaticism is treated largely as a passing tone. You may have heard the quote from Art Tatum, “You’re only a 1/2 step away from a right note”.

This is true in the Bebop era of jazz. Listen to Charlie Parker playing those long mellifluous lines. His chromaticism is used to weave in and out of the chord changes – usually at a fast tempo. Listen closely to his playing, as well of others in that era, and try to identify the chromatic points in the solo.

Also read through the transcriptions and identify the chromatic relationships. It is a good idea to listen for them first and then check to see how you did. In this era and context, there is a conception that chord changes inform the line and that there are “right” and “wrong” notes. If a soloist plays only the “right” notes, you will end up playing within the boundaries of chord/scale relationships. Clearly, many players go this route and it is helpful at the beginning, but at a certain point, contemporary jazz suggests going beyond those harmonic limitations.

The second way to approach chromaticism is to follow the history of jazz as well as your own yearning for more creativity in your playing, treating chromaticism as an infusion of color from chromatic tones. Choose a color tone and use it not as a passing tone but to incorporate it as an establishment of an interesting idea that can be developed. Bringing that particular tone into the diatonic framework will lead to a sound that needs not to be resolved.

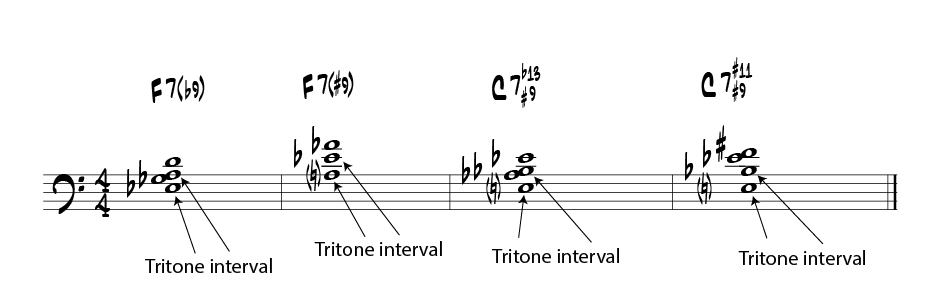

Color tones are notes that create contrast with the voicings that are built from diatonicism. Take a chord type that can more easily absorb this selection of a chromatic point such as Dominant 7th chords.

Perhaps it is because of the wideness of the tri-tone that absorb these sound to allow for the usage of a Flat 9, Sharp 9, #11, Flat 13. Listen to these voicings below…

In order to use these types of tones, pick one and insert it into your lines and/or voicings. A common mistake that many players make is to throw every alteration into their lines and voicings. This tends to make a mess of things for the very reason that adding these pitches can function as contrast. Instead, use color tones to develop a solo with a repeating musical idea. This is what is known as motivic development. A motive is a short piece of melody. (Examples, Examples Examples.) An example of that would be the beginning of Beethoven’s 5th. Pretty much every one knows that the first short idea, or motive, gets developed using repetition and modulation throughout the piece.

Usage of chromaticism is not limited to motivic development, but it does provide for one use of color tones.

While the usage of passing tones is part of an era that gave us Bebop, chromaticism is also a component of modalism. I am referring to John Coltrane’s period when he released the albums, “Coltrane” and “My Favorite Things”. The latter was a huge crossover hit and sold more jazz albums to everyone- not just jazz musicians. People whose frame of reference was Julie Andrews singing “My Favorite Things” or Danny Kaye singing “Inch Worm. Really ?? Who would have thought that?

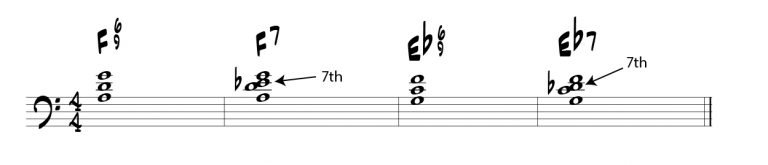

John Coltrane gives a Master Class in utilizing color tone, or chromaticism, on the recording of “Inch Worm” on the Coltrane album. McCoy uses modal interchange with the primary chords, (most repetitious in the piece) and changes them from a Major 6/9 chord to our friendly Dominant 7th chords. Listen to Coltrane’s development- how many times does he come back to playing the melody within the solo? (I think it’s 4) Each time he improvises, he stays very close to each one of the altered extensions of the Dominant 7th chord.

The use of those tones creates the environment that is inclusive to the use color tones. It’s not something that sounds like a “wrong” note that needs to resolve into the diatonic framework of the piece.

Hear the comparison between the 6/9 voicings and the dominant 7 with the 9 on top. In the comparison, I emphasize the 7th of both chords.

LeeAnn mentioned the advantage of playing single color tones rather than throwing in all the alterations.

A prerequisite to playing this way is to hear those color tones. Play an F7 on the piano or guitar and then sing the sharp 11, flat 9, sharp 9, flat 13 and so forth.

Only by hearing those notes will you be able to naturally put these more interesting colors into your improvisation. That will be your start to your improvising with more chromaticism.

Trombonist, author, marketer, & tech guy

Share this post…

I recently watched a video performance by the amazing classical pianist Yuja Chang. I’ve seen her memorizing motion and heard her virtuosic playing before, but something hit me after seeing

I have created a AI chatbot called Jazz Master Chat that draws from 75 hours of interviews from my Jazz Master Summit event a couple of years ago. I interviewed

What is jazz improvisation? Let’s first define what I mean by jazz improvisation. Jazz improvisation is a spontaneous conversation, but instead of words, we use notes. Look at two possible

My recently turned 18 year old son is a passionate photographer He 8217 s got himself a little business

A couple weeks ago I sent Richie Beirach a YouTube clip from the movie Whiplash as a bit of

I originally meant to write this as a reply to a comment Richie Beirach wrote on my blog But

Tools for helping musicians at all levels learn about jazz and play to their full capability.

Web design and marketing by:

Michael Lake @JazzDigitalMarketing.com

This is just a fake book example for the type of website I can build for you. Just trying to use a little humor here!

4 thoughts on “Getting out of the improvisation box harmonically”

LeeAnn, GREAT BLOG!! You nailed it from very interesting and varied perspectives.

I still get chills listening to Trane play inch worm. Thanks for your expertise and devotion to the music,

and thanks again Mike for initiating the whole topic.

Love it – it makes sense and an area I seek to explore, creating colors (emotions) into my solos. I hear it harmonically, just listening to the background music of movies, commercials, and musicians. Playing an emotion with a melodic instrument (my sax) is important to me and maybe more difficult, right now, understanding harmony and where and when to use passing tones, extensions, etc. My head swims trying to figure it out – but at least I hear it from a chordal instrument.

Thank you again for all that you help us with, Mike. Happy New year!

Neil

Thank you for this very helpful article.

I just finished reading it and started singing the color tones along with the F7 chord. My first reaction when I sang and played the four color tones was that they sounded very bluesy. Then I realized the four notes I was playing are part of the Ab Blues scale. I think that is one of many reasons why these notes work so well

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on chromaticism in a very easy to understand format. Can’t wait to start experimenting with the addition of a flat or #9 on a 7th chord. Always appreciate these very helpful ideas.