The Benefits of the Ear to Instrument Connection

I recently watched a video performance by the amazing classical pianist Yuja Chang. I’ve seen her memorizing motion and heard her virtuosic playing before, but something hit me after seeing

Categories:

Categories:

I was recently party to a heated email conversation between two very famous jazz teachers/players who hold polar opposite views on how one becomes proficient in learning to improvise jazz. I want to share with you clues I found in the writing of one of them that uncover a fundamental mistake. It’s an error in thinking that leads his disciples down a dead end that if they discover it at all, may sadly be too late.

I align myself strongly with the other side of this argument, and have written much against one aspect of it – the school of quick, easy, and effortless attainment of jazz proficiency within this article as well as this one.

Highlighted within the email discussion was another aspect of this method which I think is equally if not more damaging to students: this educator’s method relative to the role of the mind and one’s ego in developing proficiency in playing jazz.

I’m avoiding the word “mastery” and instead using “proficiency” because what I have to say pertains not just to those who aspire to master the art of jazz, but also for those who wish to play as well as their time and talent permit. The critical question for anyone wishing to play jazz better today than they did yesterday is: how best do I spend my practice and performance time?

One line within the email of the educator with whom I disagree exposes a fundamental error in his method. He wrote that his method involves “separating the mind from the body and separating the ego from the mind.”

This is not a novel idea. the philosophical battle between mind and body has raged for thousands of years. Instead of seeing mind and body as an integrated whole, the position of this jazz educator is that the mind interferes in the artistic process and that the body should be left on its own to operate the instrument.

But the body absent of a mind is little more than a zombie calling jazz the twitching of its fingers fluttering randomly across the piano keyboard. Instead of putting in thousands of hours of mindful practicing, this view believes in some higher power that can operate a complex musical instrument, somehow in the end, creating pure art unsoiled by effort and ego, and as a result, free of the responsibility of doing and thinking.

This position is further confused when he advocates “separating the ego from the mind.” Earlier, he advocated separating mind from body, so what role does the ego-less mind even play in this zombie process?

This educator’s confusion over the relationship between mind and body is later demonstrated when he describes the purpose of repetition as reaching the point where “the mind withdraws but the body plays.”

But the mind, or ego, never withdraws. Instead, a different role for the mind takes over. Rather than conscious thinking and directing from note to note along with the obsessive and distractive thinking over what one just played or is about to play, the subconscious mind becomes the autopilot armed with a lifetime of practiced skills.

An airplane on autopilot does not disappear from the sky. It still has the same shape, colors, and markings, the passengers are still on board, and the destination is still the objective. The change is that the pilot is no longer manually steering the aircraft. The plane knows exactly where to fly without the pilot’s hands on the wheel or feet on the rudder controls.

The subconscious artistic process is anything but ego-less. That automated part of your subconscious mind is telling your personal story, with your particular tone and inflections, wrapped within your unique treatment of time (swing). It is perfectly reflecting your ego or self.

Further on within the email, this educator claims that his method places “no expectations” on the player. This is again an abandonment of the ego.

Expectations, however, are exactly what is necessary for any musician expecting to attain proficiency. Back to the autopilot example, the absence of expectations is like having no flight plan, written or otherwise. Where will that plane travel? Does it have enough fuel? Will there be a suitable place to land? What will you do when you arrive? If it crashes, surly no one is to blame!

What is the result of having no expectations for your playing? No direction, no objective, and no standard. I guess that means that without any skill whatsoever in playing sax, my infantile squeezing of vibrations from a reed should be evaluated no better or worse than the playing of Michael Brecker. Without expectations, anything goes and any evaluation of good or bad is thrown out the window. Worse yet, evaluations are considered irrelevant

The scorn of ego in our modern world unfortunately carries a lot of popular appeal. That scorn manifests itself in the denigration and envy of successful businesspeople, the popularity of the anti-hero in novels and film, the worship of formless non-objective modern art, the west’s inability to decisively defend its values morally or militarily, the declining state of our educational institutions and so much more. I would like to believe that we can at least prevent ego-contempt from polluting the art of jazz!

Instead of following gurus who preach the absence of ego as a means for you to play jazz at some high and mystical level, embrace those personal attributes that define you and your music. Be proud of your abilities, work ethic, and aspirations. Embrace your ego, and develop your ability to practice consciously and purposefully, then within your performances, allow your ego to speak through the automatized workings of your subconscious.

It is there where your abilities will flourish and find their highest expression.

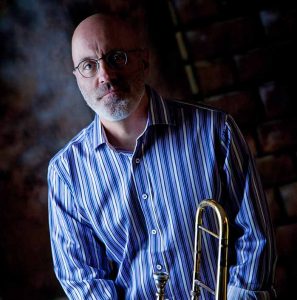

Trombonist, author, marketer, & tech guy

Share this post…

I recently watched a video performance by the amazing classical pianist Yuja Chang. I’ve seen her memorizing motion and heard her virtuosic playing before, but something hit me after seeing

I have created a AI chatbot called Jazz Master Chat that draws from 75 hours of interviews from my Jazz Master Summit event a couple of years ago. I interviewed

What is jazz improvisation? Let’s first define what I mean by jazz improvisation. Jazz improvisation is a spontaneous conversation, but instead of words, we use notes. Look at two possible

My recently turned 18 year old son is a passionate photographer He 8217 s got himself a little business

A couple weeks ago I sent Richie Beirach a YouTube clip from the movie Whiplash as a bit of

I originally meant to write this as a reply to a comment Richie Beirach wrote on my blog But

Tools for helping musicians at all levels learn about jazz and play to their full capability.

Web design and marketing by:

Michael Lake @JazzDigitalMarketing.com

This is just a fake book example for the type of website I can build for you. Just trying to use a little humor here!

3 thoughts on “The illusion of ego-less jazz”

Mike, another great post !! You are consistently hitting it out of the park these days with your blogI

I wish more real educators would step up and speak up about their true thoughts on the self-help quick shortcut pop culture crap that successfully floods the jazz education market and gives interested students of our great music of jazz the wrong and incomplete guidance necessary to become their best musical selves.

There is no such thing as mastery without ego !! There is of course the appearance of ego-less mastery after years and decades of concentrated practice, hard work, analysis, and reflection. Consider Jack DeJohnette’s masterful drum solos or Glenn Gould’s playing of Bach’s Goldberg Variations. Mastery, of course, can exist in many areas outside of music. Just look at Roger Federer’s backhand or Michael Jordan’s unblockable fall away jump shot.

Because at full maturity they made their particular effort look easy, their effort can be misinterpreted as the body taking over without the mind. But imagine any of their competitive or artistic drives without their strong ego. Imagine any of their relentless practicing or performing without any evaluation. It feels silly to even contemplate.

I love the truth. Thanks for pointing out the fallacies of this so-called egoless jazz fantasy. I hope people are listening.

Richie Beirach

Hessheim

Germany

I think one reason people believe that the body can work great artistic and athletic feats without the mind or ego is that the body is something we can all observe. The workings of the mind, ego, or self is invisible to the observer.

Like you wrote, it does seem silly to imagine the body operating without the mind but I think that belief comes from lazy thinking. It’s just unfortunate that so many people are being convinced of it.

totally agree !!